From Board to Battlefield: The Social Dynamics of the Lewis Chessmen

For centuries, the enigmatic Lewis Chessmen have captured the imagination of historians, archaeologists, and art enthusiasts alike.

These iconic artifacts, found on the Isle of Lewis in Scotland, not only offer a glimpse into medieval life but also raise intriguing questions about their origins and purpose.

Let’s dive into the fascinating story behind these remarkable chess pieces.

The Lewis Chessmen are a fascinating glimpse into medieval life, art, and societal structures. These intricately carved chess pieces, discovered on the Isle of Lewis, are not just relics of a bygone era but vivid reflections of a complex world of trade, hierarchy, and cultural exchange. Let’s explore their story under six key themes.

Origin

The Lewis Chessmen are widely believed to have been crafted in Norway, likely in Trondheim, a renowned center for ivory carving during the 12th century. Made primarily from walrus ivory and whale teeth, these pieces reflect the skill and cultural artistry of their time.

Their journey from Norway to Scotland likely followed established trade routes connecting Scandinavia with the British Isles. During this period, the Hebrides, including the Isle of Lewis, were under Norse control, making them a natural stopping point for goods and travelers. The chessmen may have been transported as part of a merchant’s wares, intended as a luxury gift or personal possession.

Interestingly, similar Nordic artifacts, such as decorative combs, brooches, and other ivory carvings, have been found across the UK, attesting to the extensive trade and cultural exchanges between the Norse and the British Isles. Why the chessmen were buried in Lewis remains a mystery—were they hidden for safekeeping or abandoned? Regardless, their preservation in Scotland offers a unique opportunity to study this intersection of cultures.

Discovery

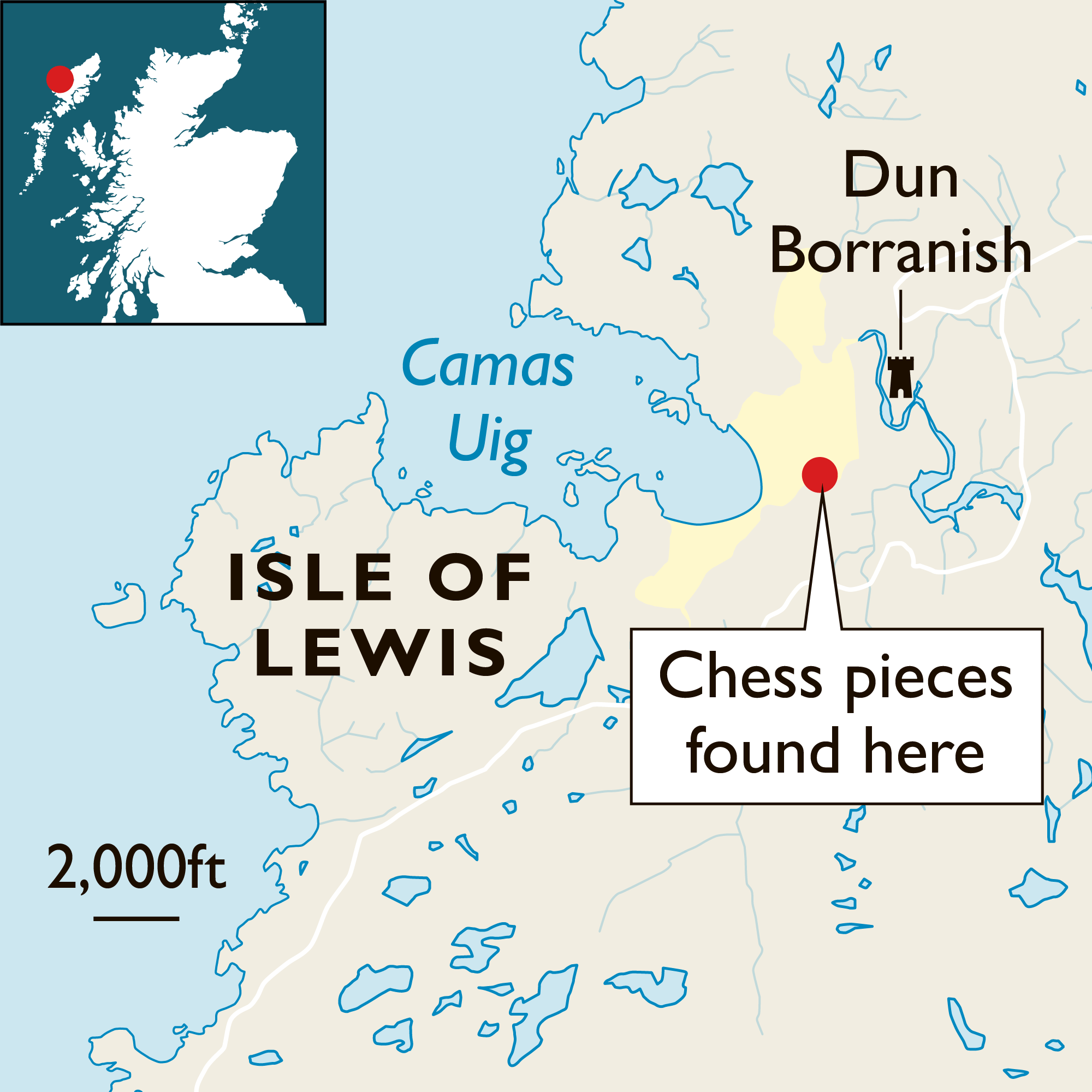

The Lewis Chessmen were discovered in 1831 near Uig on the Isle of Lewis, buried in the sand dunes. While the exact circumstances are debated, one account suggests that a local shepherd found the hoard while digging in the dunes. The discovery included 93 items: 78 chess pieces, 14 tablemen (used for a different game), and one belt buckle.

The precise location of the find has been disputed, with some suggesting alternate sites in the region. This uncertainty has added an air of mystery to the chessmen’s story.

Today, the chessmen are divided between the British Museum in London, which houses 82 pieces, and the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh, home to 11. This division has sparked debates over their rightful home, with many in Scotland advocating for their full return as symbols of Scottish-Norse heritage.

Chess: A Medieval Cultural Phenomenon

Chess was introduced to Europe from the Islamic world around the 9th century and reached England via Spain by the 11th century. It quickly gained popularity among the European aristocracy, becoming a favored pastime and a tool for education.

The game’s structured rules and emphasis on strategic thinking made it an ideal way to teach governance and military tactics. Nobles and rulers used chess as a metaphor for power and decision-making, training young leaders in the art of planning, foresight, and negotiation.

The Lewis Chessmen exemplify this cultural phenomenon. Their intricate design and the sophistication of their craftsmanship suggest they were created for wealthy or noble patrons who valued chess as both entertainment and a marker of intellectual refinement.

Power Symbols

The Lewis Chessmen are more than mere game pieces; they are symbols of power and prestige. Their size, detail, and material—carved from exotic ivory—signify their owner’s wealth and status.

Beyond their material value, the chessmen reflect the medieval worldview. Each piece represents a specific societal role, mirroring the hierarchical order of the time. This hierarchy wasn’t just about governance but also reinforced ideas of divine and social order. The prominence of bishops among the pieces, for instance, underscores the Church’s central role in both spiritual and temporal power.

The chessmen also embody cultural exchanges, blending Nordic artistic traditions with the European passion for chess. They highlight the interconnectedness of medieval societies, where ideas and customs flowed across borders as freely as goods.

Reflection of Society

Each type of chess piece in the Lewis Chessmen tells a story about the layers of medieval society:

Kings and Queens: These figures represent the pinnacle of authority. The kings are imposing and regal, while the queens are often depicted in contemplative poses, symbolizing their advisory roles and strategic importance.

Bishops: As religious leaders, bishops signify the Church’s immense influence, serving as both spiritual guides and political advisors in medieval governance.

Knights: Mounted warriors embody the martial class, tasked with defending their lords’ territories and maintaining order through force. Their depiction on horseback emphasizes mobility and strength.

Rooks: Often represented as castle-like structures or fierce berserkers in the Lewis set, rooks symbolize fortification and the militaristic might of feudal lords.

Pawns: These simple, unadorned figures represent the common people. In chess, their advancement reflects the possibility of upward mobility, albeit rare, mirroring the aspirations and struggles of the lower classes.

Modern Day

The Lewis Chessmen are celebrated today as masterpieces of medieval art. Visitors can view 82 pieces at the British Museum (Room 40, Medieval Europe Gallery) and 11 pieces at the National Museum of Scotland (Kingdom of the Scots Gallery, Level 1, Case K5). Their expressive faces and intricate details continue to captivate audiences worldwide.

Similar carved ivory artifacts have been discovered, though none match the scope and completeness of the Lewis hoard. The chessmen’s significance has sparked ongoing debates about their repatriation, with calls for their full return to Scotland reflecting broader conversations about the ownership and stewardship of cultural heritage.

Conclusion

The Lewis Chessmen are far more than beautiful objects; they are a window into a world of trade, strategy, and societal complexity. Their journey from Nordic workshops to a windswept Scottish island exemplifies the interconnectedness of medieval Europe.

Whether you visit them in London or Edinburgh, the chessmen remain a testament to the enduring power of art to tell stories about the past. They are not just relics of a game but symbols of a time when the moves on a chessboard mirrored the strategies of life and power itself.